From Les Turnbull’s book ‘A Celebration of our Mining Heritage’.

ISBN 978-0-9561248-2-1

John Buddle Takes Control

In 1807, John Buddle Junior became the principal viewer at Heaton Colliery – a position he held until 1821. Like many viewers he also had a small share (9/96th) in the enterprise he managed. At the age of six, young John was taken underground by his father, the viewer of the collieries of the Dean and Chapter of Durham Cathedral, to begin to learn the skills of his trade; and throughout his life he argued that an early introduction to pit life was important if boys were to acquire that sixth sense which made the job of a miner safer. Besides being head viewer at Heaton, John Buddle was viewer at several others collieries including Wallsend, Benwell, Walker and the collieries of Lord Lambton. In the early nineteenth century, he was regarded as one of the leading authorities on mining practices and his advice was sought at several parliamentary inquiries. He also acted as secretary to the Northumberland and Durham Coal Owners’ Association.

The Engine Shaft December 1814

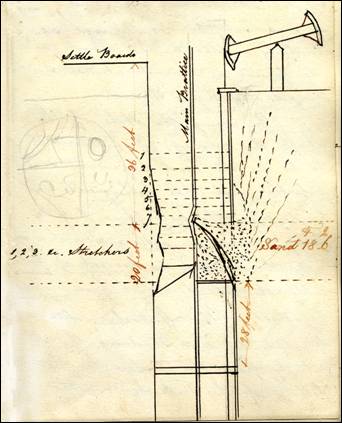

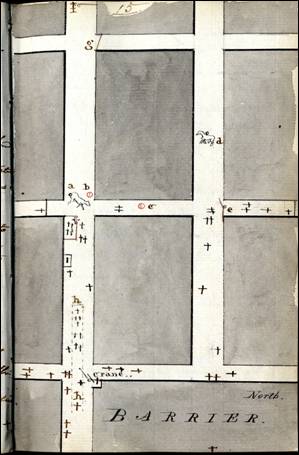

Just how precarious a business mining could be is revealed in Buddle’s view books. In January 1810, he records that the ‘E’ Pit at the Spinney caught fire and ‘had not the fire gone out itself I do not think it could have been extinguished by the engine or any other means…without drowning up the Colliery which from the fire being situated so much to the rise would have taken 9 or 10 months to accomplish and in the meantime the pit must have been torn to pieces by repeated explosions’. In April 1813 the ‘E’ Pit was threatened with another catastrophe, creep, or the lifting up of the floor caused by the pressure on the pillars. Under such circumstances, the coal becomes crushed and cannot be worked except by dangerous and expensive methods. Buddle ordered all the men, horses and materials to bank and coal production from this pit was abandoned until 1816. An event which threatened the existence of the ‘A’ Pit occurred on 6th December 1814. Buddle recorded that ‘the timber at the quicksand broke completely in the old Engine shaft this morning and the pit is in danger of being lost…as there is now no other prospect than a long interruption of coal work set about distributing the men and boys to neighbouring collieries’. He made a sketch in his view book showing the bed of sand and the damage caused by the collapse. There is also a rough plan of the famous triple shaft drawn in pencil on the left hand side.

The threat to their livelihood worried the men, spurring some into action to try to save the colliery, as Buddle recorded: ‘William Gardner, Ralph Witherington and his two sons were so alarmed at the idea of giving up the pit that they volunteered to attempt to put her thro’ the sand by short lengths of timber; and offered to give their labour if the owners would find timber etc. This I consented to, subject to the approbation of the owners, and they promised if they succeeded in securing the shaft thro’ the sand – 8 or 9 feet in diameter – that they should have a present of £50 over and above their wages’. The men were successful and on Friday 6th January 1815 Buddle ‘put the horses down the old pit again, finished the heapstead and got all in readiness for drawing the coals tomorrow so that we may be ready for coal work on Monday morning’.

There are many references in Buddle’s view book to the problems with water and the pumps in the colliery. A steam engine had been installed at the ‘A’ Pit but at first horses were still used to power chain pumps at the Middle (‘C’ and ‘D’) and Far (‘E’) pits. In May 1808, Buddle recorded that two horses were being used at both the ‘D’ Pit and ‘E’ Pit for drawing water. However, in July 1813, Buddle ‘bought the Penshaw Engine of Mr. Lambton for £2,200’ for pumping at the Middle Pit and declared that ‘the object of erecting this engine is not only to ensure the working of the whole coal in west of the old pit but also to attempt the draining of old Benton or Heaton Wastes or perhaps both’. An ambitious plan indeed! Unfortunately, on 15th April 1814, the ‘boiler of the new engine at the ‘D’ Pit burst killing Jas. Young and Geo. Shelaw – putters. They happened to be standing near the Fire Door at the time. Walter Blackett, the fireman, was so severely scalded that his life is despaired of’.

Many other accidents are recorded in Buddle’s diary. On Sunday 14th November 1813, he noted that two men were injured by exploding methane gas through carelessness: ‘Tim Dodgson, overman, and Geo. Robson, deputy, burnt this morning in the north exploring drift of the old pit…In going their rounds Dodgson and Robson went into the drift without looking at their candles and when near the face were fired upon unawares…Robson was severely burnt but Dodgson received little injury. The fire happened entirely through the carelessness of the parties themselves’. In February 1814, an explosion killed three trapper boys – ‘Hall, Richardson and Short had wandered up the drift despite warnings of gas’. Buddle showed no sympathy for those who suffered as a result of their own neglect. These isolated incidents of injury and death were typical of life in the mine but on the morning of 3rd May 1815 an unusual event took place resulting in the deaths of 75 men and boys. At 4-30 a.m. Heaton Main Colliery was inundated when men on the fore shift broke into the flooded workings of old Heaton Banks Colliery. John Buddle took charge of the rescue and his diary records the daily struggle to save his workers. It is the classic tale, common in the history of mining accidents, of bravery, comradeship, self sacrifice, unheeded warnings and sheer misfortune.

Inundations were not uncommon in the mining industry. The parish records of St. Andrew’s record that on ‘24th April 1695 were buried James Archer and his son Stephen who in the month of May 1658 were drowned in a coal pit in Galla Flat by breaking in of water from an old waste’. One hundred years later, in 1796, miners in East Denton Colliery broke into the flooded workings of an old mine at Slatyford and six men were drowned. After this tragedy, William Thomas, Mrs Montagu’s viewer, suggested to an audience at the Literary and Philosophical Society in Newcastle that plans of abandoned workings should be housed with the Justices of the Peace to avoid such disasters in the future. Unfortunately, for the miners at Heaton Colliery, his request fell on deaf ears and many years were to elapse before this obviously sensible measure was put into effect. Miners did not have a monopoly of dangerous working conditions: many would argue that the men who transported the coal in small collier vessels down the east coast had a more difficult task. But when a major disaster occurred, such as the explosion at Felling or the flooding at Heaton, then a large loss of life resulted bringing their danger to the attention of the nation.

The Last Shift

May Day was over and the great festival of Spring had passed.

Tuesday, the second, was just another ordinary day.

The sun had set and, by late evening, Heaton’s farming community was at rest.

Only the mine disturbed the silence.

In the darkness after midnight,

Numerous figures thread their way through the blackened fields,

Marshalled to their workplaces by the beat of the great engine,

The pulse of the colliery.

To the outsider,

The mine is an awesome place,

Full of magical sights and sounds,

Another world, gripping the imagination.

Small fires light up the pithead

And the acrid smell of burning coal pervades the air.

The noise, the drifting smoke and the flickering lights

Add to the mystery.

The rhythmic power of the massive engine is compelling.

The deafening thuds and hissings command attention.

Amid this inferno,

Men and boys exchange banter,

While they wait to be lowered, in wicker baskets,

Down into their underworld.

All are unaware of the impending disaster,

And the acts of heroism,

Which ordinary men would soon perform.

Most will not escape

Before torrents of water overpower the great engine

And destroy the mine.

Summer will pass,

And the ice of winter grip the ground,

Before their bodies are found.

Men and boys will be returned, lifeless,

Through frozen fields, now white with snow,

To their final resting places.

This was their last shift. (Les Turnbull)

The Flooding of Heaton Main Colliery – Wednesday 3rd May 1815

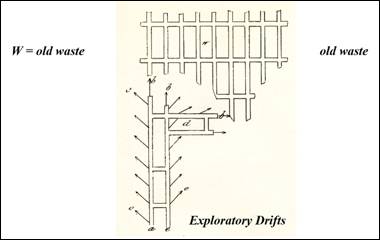

On that fateful morning in May 1815, there were one hundred and one men and boys underground on the early shift under the direction of William Miller, the under viewer. In the far west of the mine, about a mile from the Engine Pit, John Bell and Andrew Caldwell were working with their putter boy, William McCoy, in an exploratory drift beneath the old village of Heaton. The drift was being driven northwards in stone from the north west mothergate of the Engine Pit to locate the High Main seam beyond an upcast dyke. Although the position of the abandoned workings of Heaton Banks Colliery in the west of the royalty was known, there was no detailed plan of the old mine; and, as was customary in such circumstances, a series of borings was ordered to determine the position of the flooded waste in order to retain a barrier to protect the new workings. The method of driving these drifts was later explained by Matthias Dunn, who was one of John Buddle’s apprentices in 1815; and the diagram below is based on his drawing.

An Exploratory Drift

Dunn noted that ‘Boring is frequently resorted in coal workings in which a waste w is expected, the bearings of which are uncertain. These borings are necessarily horizontal, and, as they might perchance be approaching a part of the workings of irregular shape, a pair of drifts a are pushed on in advance of the main workings. In the leading drift a direct hole b is kept usually six or eight yards in advance…flank holes cc are bored on each side to a similar length, such bores being resumed at every five or six yards. As the consort drift e is kept a few yards behind the leading drift, some of the holes may be safely dispensed with. As soon as a perforation of the waste occurs, the bore ought to be carefully plugged with wood; a new position should be taken up twenty or thirty yards back, and new boring drifts at right angles made right and left until the position of the waste be completely ascertained, and within which lines all the interior workings may be considered safe’. Dunn concluded ominously that ‘notwithstanding these precautions, whether from occasional neglect or unforeseen accident, inundations have frequently taken place’.

For several months past, the borers in Heaton Colliery had located the waste along an extensive line by repeated holings. By 3rd May, the face of their drift was 180 yards south of the old Chance Pit of Heaton Banks Colliery, which was about 100 yards due east of the old windmill in Heaton Park. In today’s geography, the men were working about 330 feet beneath St. Theresa’s School. During the previous week the drifters had reached the bottom of the coal seam and the two men were now pushing the drift forward to give full access to that seam. The coal near the dyke was weak which was not unusual. At about 4.40 a.m. William Miller, visited the men who pointed out that there was a greater bleeding of water than usual coming from a weak point in the coals on the western side of the drift. Miller was not unduly alarmed and ordered that another two feet of coal should be taken. Then the nine o’clock shift would make another trial bore. After leaving the drift, Miller met Tim Dodgson, an overman in the old pit, who asked him to ride to the surface; but Miller replied that he was going to stay underground since the wastemen were waiting to go into the old waste with him. About fifteen minutes later, a discharge of water ‘like the spout of a garden pot’ took place ‘with a hard hissing noise’ about two yards from the face of the drift. This event still did not alarm the men who continued with their work.

However, when the coal was removed, the feeder increased in size making a noise louder than a steam engine. Therefore, Bell and Caldwell came out of the drift and sent their putter boy to warn the people at the cranes. Both men waited at the old crane which was about 110 yards from the face of the drift. After a short time, John Bell decided to go back to see the state of the drift; but just as he reached the door into his workplace, the water broke in with the noise of thunder and the wind blew him down. Because the coal seam dipped to the east at an incline of about one in ten, the water cascaded towards the shaft – their only escape route. Bell hurriedly returned to Caldwell and they scrambled to the shaft with their putter boy accompanied by William Holt, a rollyman. This was a journey of about 1,500 yards which was made more difficult because the wind had extinguished their candles. They were followed by the onsetter, John Pratt, by fifteen rolly drivers and trappers, and the rollymen, William Rutter, Thomas Carr and Thomas Wilkinson. The hewers Thomas Curtis and Joseph Harrison were the last to reach the shaft before the rising waters sealed off the only escape route. Seventy five men and boys were trapped in the upper part of the mine.

Almost immediately after the accident had happened, the Chance, Old Engine, Thistle Bank, Knab and Venture pits of old Heaton Banks Colliery fell in. After the closure of the mine in 1745, these pits had been sealed off and their surroundings planted with trees as was the custom in the mining industry. The Chance Pit, which was the nearest to the trapped men, appeared to be open nearly to the bottom. Hurriedly, balks were laid across and preparations made for securing the top of the shaft to attempt a rescue. However, at about 5.00 p.m., the large bed of sand about thirty feet down broke away and by 8.00 p.m. it had filled the pit ending the first rescue attempt. This was the same bed of sand which had nearly destroyed Heaton Main Colliery six months earlier.

Despite three large pumping engines being employed, one of which was 130 horsepower, by Thursday afternoon the water had risen 183 feet up the Engine Pit shaft in East Heaton, after which it began to fall. The water also cut off access to the men from the Middle Pit and the Far Pit. From various calculations that were made, it was determined that the water could rise 240 feet up the Engine Pit shaft before it would reach the face of the workings in the rise part of the mine and drown the trapped men.

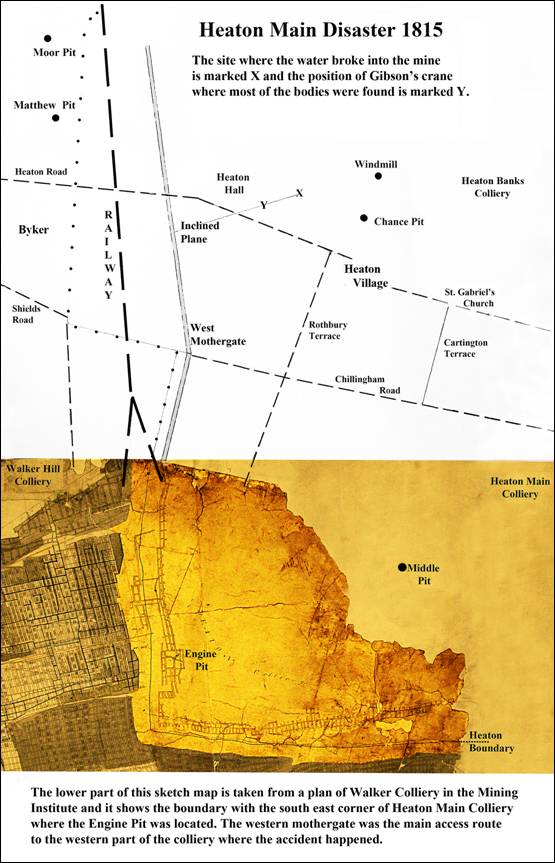

Composite Plan of Heaton Main Colliery

Figure 35 is an attempt to illustrate the geography of the disaster. The bottom part is the only surviving information of the plan of Heaton Main Colliery shown on a plan of Walker Colliery. The upper half is a projection based upon this surviving fragment and information provided in the view books of John Buddle. The location of the East Coast railway and the some of the present roads, such as Heaton Road, Shields Road and Chillingham Road, are shown as reference points. North is on the right hand side.

After their failure to reach the men from the Chance Pit, the rescuers then turned their attention to the old pits of Byker Colliery situated to the north of Shields Road beyond the southern boundary of Heaton royalty. On Friday morning borings were made to find the Matthew Pit without success. However, in the evening another pit, which Buddle wrongly believed to be the Kenton Pit, was found. He later realised that it was the Moor Pit. [1] Immediately, work began to clean out this old pit but the air was so bad that William Patterson, one of the rescuers, was nearly suffocated. This setback brought the rescue operations to a temporary halt.

On Tuesday 9th May, air boxes were put into the Moor Pit to improve the ventilation and by Wednesday the wind was blowing so strongly from the west that air in the shaft could be kept fresh. A small air pump was brought from Wallsend to apply to the boxes in calm weather. By Saturday 13th, John Buddle was able to get down the Moor Pit and advance 52 yards along the north headway towards the trapped men. A further 40 yards progress was made on Sunday and the next day the rescuers got to the most northern part of the old workings in Byker Colliery. They were now almost beneath the boundary line between Heaton and Byker – roughly beneath the Molineux Medical Centre in today’s geography. The rescuers believed that they were about 97 yards from the nearest point in the waste of Heaton Main Colliery which would give them access to the trapped men. Soon hope turned to despair. On Saturday 20th, a great discharge of foul air forced the men to abandon the rescue attempt. By now, almost three weeks after the inundation, Buddle realised that there was no chance of the men being found alive. The rescue was called off and all the miners were transferred to Wallsend Colliery, except two deputies, who were left to keep watch at Heaton.

The men and boys had been lost and John Buddle’s task was now to win back the colliery. His view book records the daily struggle to keep the pumping engines in action. His comments on 15th July is one typical entry: ‘the Far Pit Engine has gone very little this week on account of the badness of the boilers; but thorough repair of the middle one being completed, and the other two being cleaned and repaired in a temporary way, the engine got to work again last night. The Middle Pit Engine has also gone indifferently all week from the bad state of the boilers’. There are frequent references to borrowing spare parts from other collieries in the neighbourhood; and there are many examples of the engineer’s ability to improvise when confronted with an emergency. On Thursday and Friday 5th and 6th of October, for example, Buddle was ‘occupied these two days in adapting the travelling Engine (Chapman’s railway locomotive) to draw the rubbish with chains at the Middle Pit’.

Gradually, the water subsided. On Tuesday 19th October, Buddle was ‘down the Far Pit and was able to take candles all round’. The following Thursday, he ‘lighted the Far Pit furnace without difficulty’, a task which was necessary to secure the proper ventilation of that part of the colliery. A month earlier he had been able to enter the Middle Pit where ‘all about the shaft was a complete scene of ruin’ which Chapman’s engine subsequently cleared. By late October, work was well advanced in ridding out the west mothergate in the Middle Pit. The final entry in his view book for 1815 records that ‘the water was so low in the Old Pit this morning as to allow a sight of the tops of the full corves standing on the rolleys near the shaft’.

On New Year’s Day 1816, he observed that ‘the water had lowered 2 feet in the old pit this morning which left only about a foot on the rollyway. Jas. Smith and Jobe – enginewrights – went up the west mothergate to the entrance of the stables and found good air going. Saw two horses in the rollies at the shaft siding – they were entirely reduced to skeletons without any offensive smell, except when the sleek near them was disturbed’. The following morning the water was down to the level of the rollyway and Buddle went underground to examine the state of the pit accompanied by six miners. The group was able to travel about ninety yards up the west mothergate where a large fall stopped their progress. They attempted to by-pass the fall by using the stable board to the south where the rollyway seemed to be clear but Buddle was cautious. He decided that no attempt should be made to access the workings until the debris around the shaft was cleared.

On Saturday the 6th January 1816, some eight months after the inundation, the first body was found. William Stott, aged 79, the furnace keeper, was discovered about 200 yards from the Middle Pit shaft in the stoneway linking it with the Engine Pit. ‘The body was found under a fall with nothing but the head out; the features were visible but the head had a chalky appearance and the body was reduced to a mere skeleton, the bones being held together by clothes’. The following day William Stott was buried at Wallsend parish church and work continued to recover his workmates.

By 19th January the debris from the fall in the west mothergate of the old pit had been cleared. The next day the body of William Miller, the under viewer, was found in the west mothergate, two yards west of the stoneway end. One of his feet was fast between a plank and the top of a corf and his body was entangled amongst the corves. Buddle noted that ‘the head was towards the pit and he appears to have been entangled in the act of escaping’. The bodies of the wastemen Robert Richardson, Henry Dixon and Arthur Dixon, were found on Tuesday 23rd in the west mothergate lying four or five yards west of Miller’s body. The mothergate was blocked beyond this point and it took until Sunday 4th February to clear the fall. The body of George Laws was found that day at the bottom of the inclined plane. Near to this spot, two days later, Lancelot Nicholson’s body was found covered in rubbish – his clothes had been torn off and his body severely mangled. The bottom of the inclined plane was covered in rubbish several feet thick and the plates in the upper part were torn up which was all evidence that an immense torrent of water had rushed down.

The men were employed for the next week clearing the rollyway from the Old Engine shaft to the bottom of the inclined plane. On Wednesday 14th February, Richard Hepple and Robert Smith led a group of men into the workings and discovered fifty five bodies at Gibson’s crane. Buddle commented that ‘they had evidently survived the accident for some time as they had killed a horse and cut the flesh out of his hams – it had been divided amongst them but little had been eaten as portions of it, seemingly the share of individuals, was found lying near the bodies in caps and bags’. The positions of the bodies found near Gibson’s crane at the top of the inclined plane are marked with crosses on the sketch from Buddle’s view book reproduced below. The horses killed for food are drawn at ‘a’ and the crane hole ‘h h’.

By Monday 19th February, the rollyway had been cleared sufficiently to get the bodies out from the area around Gibson’s crane. Buddle commented that ‘they were not so much decayed as might have been supposed – those which lay amongst any water were the worst. The body of a boy, which was covered with water in the crane hole, was a mere skeleton’. He concluded that ‘they had evidently died of suffocation’. When, on 5th May 1815, the men had broken through from the Moor Pit, they had created a free communication of air between the Moor Pit and Gibson’s crane. It is probable that this attempted rescue ‘put a period to their existence by letting the air which was highly compressed escape’ from the trapped men. The pit was closed on Tuesday and Wednesday for the funerals of these victims. Fifty one bodies were buried in the south east corner of St. Peters Church in Wallsend; the other four at St. Bartolomews in Longbenton. Although the graves do not survive, their deaths are recorded in the parish registers and recently a commemorative plaque has been placed in the church porch at St. Peters.

The Location of the Victims

Meanwhile, the grisly task of recovering the corpses continued. The body of old Edward Gibson was found on Thursday 15th in the first stable board just on going into the stables. It was lying on top of some timbers, nearly at roof height, with the clothes mostly torn off. On the following Thursday, Shipley Mitchinson’s body was found nearby ‘near to the roof and…the clothes nearly all torn off’. Buddle concluded that ‘it is clear that the four wastemen and Miller, together with old Gibson, had been altogether. Robert Richardson, as well as Gibson, were two feeble old men and it is probable that Miller and the other wastemen had perished in consequence of assisting them out – they were all within 100 yards of the shaft’. The final eight bodies of the hewers, William Southern, Edward Robson, Simon Dodds, John Reay and Matthew Johnson, together with their putters, Anthony Southern and William Hall, were discovered at the face of the far south west board on Wednesday 6th March. The craneman, Thomas Miller, was with them. On 7th March Buddle recorded in his view book that ‘nothing done underground today on account of the Coroner’s inquest on the bodies and the funerals’.

On 8th March, Richard Heppell and Thomas Smith travelled all around the Engine Pit with candles and were able eventually ‘to enter the drift where the waste burst in with a lamp of Sir Henry Davy’. This is noteworthy because the safety lamp had only been demonstrated on Tyneside in the previous January, four months earlier, and its early use at Heaton is another indication that the Heaton Main Colliery was at the forefront of technological developments. ‘They saw the feeder of water which seemed small’. The drift had struck a corner of a pillar which had given way under pressure from the water. Buddle reckoned that if the exploratory drift had been four feet further east the accident would not have happened: chance once again played a part.

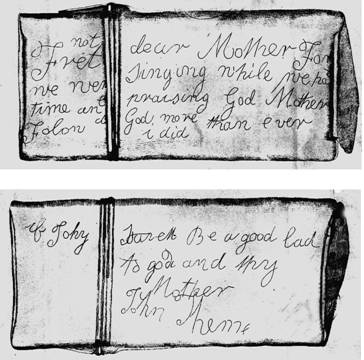

Their Last Messages

The relatives were required to go down the pit to identify their husbands and sons since the bodies were so decayed that moving them to the surface would have destroyed the evidence. Elizabeth Thew, whose youngest son John had survived, was looking for her husband, her eldest son George and her middle son William. She recognised William by his auburn hair and found his tin candle box in one of his pockets. On it was inscribed his last message: ‘Fret not, dear mother, for we are singing while we had time and praising God. Mother follow God more than I ever did’. On the other side was a message from her husband: ‘If Jonny is saved, be a good lad to God and thy mother’. Her desperate circumstances are difficult to embrace.

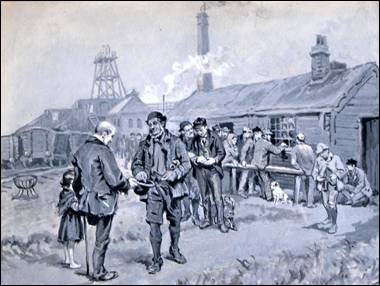

The message was to be used in a pamphlet entitled ‘A Letter from the Dead to the Living’ to raise money to support Mrs Thew. William was described as a scholar at Byker Sunday School and he also attended Mr. Swallow’s evening school in Catterick Buildings at Byker where he learnt to write. In an age before the welfare state widows and orphans had to reply upon public charity. As was the custom after mining disasters, the public were invited to subscribe to a fund to support those reduced to poverty by the accident. On 30th May 1815, The Times published an appeal. Contributions were received not only from coal owners and workmen in the locality but also from further afield including members of the Coal Exchange in London; but, although the public were generous in their support, the fund was only a temporary measure. In 1843, the letter from the dead was republished to raise money for Elizabeth Thew, who by then was an impoverished widow living in an attic in Byker. Although drawn later in the nineteenth century, Ralph Hedley’s picture of payday, showing an injured miner begging for support from his workmates, is a reminder of how tough life could be for those who survived with injuries.

Payday by Ralph Hedley

By March 1816, preparations were in hand for the re-opening of the colliery. The stables had been cleaned and whitewashed and on 9th March sixteen horses were lowered down the Engine Pit. Two days later the bodies of Ralph Widdrington and his younger son Henry were discovered – these were the last victims of the flooding recorded in Buddle’s view book. However, other minor accidents continued to happen: Tim Dodgson, the overman who had narrowly escaped the inundation, was killed drawing props on 21st August; and on 18th December Arthur Wilson, the rolleyway keeper, was crushed to death. The words of Sid Chaplin, himself a miner, are a reminder of the price paid in injury and death by the men and boys working in the coalmines.

‘Twenty lads, so hearty, went down the pit

Today.

Twenty lads, once hearty, will never again draw

Pay.

After the Heaton accident, two great engineers of the day, William Chapman and John Buddle, who were companions of William Thomas at the Lit & Phil, resurrected the idea that plans of mines should be housed with a public body to avoid similar accidents in the future; but again without success. The Mines Act of 1850 made it compulsory for managers to keep a working plan of the colliery and make it available to government inspectors but there was no requirement to deposit plans of abandoned workings until 1872. The legislation was not retrospective and in March 1925, miners at the View Pit in Montagu Colliery broke into the flooded workings of the Brockwell seam in Benwell Colliery, which had been abandoned in 1848. This resulted in the deaths of 38 men and boys.

[1] Buddle later noted that ‘the proper name of this pit appears by an old plan to be the Moor Pit’ described as ‘an ancient pit in front of Heaton Hall’. The Moor Pit is shown to the west of the Matthew Pit on Fig. 8.

A diary of 1815, the wider picture:

- 2 January Lord Byron marries Anna Isabella Milbanke, Seaham, County Durham.

- 2 January The Prince Regent divides the Order of the Bath into three classes: the Knights Grand Cross, Knights Commander and Companions.

- 3 January – Austria, Britain and Bourbon-restored France form a secret defensive alliance treaty against Prussia and Russia.

- 8 January – War of 1812: Battle of New Orleans – American forces under General Andrew Jackson defeat the British in the last major battle of the war.

- 15 March – Corn Laws passed by Parliament.

- 13 February – The Cambridge Union Society, one of the oldest debating societies in the world, founded at the University of Cambridge.

- 30 May – The East Indiaman Arniston, repatriating wounded troops to Britain from Ceylon, is wrecked near Waenhuiskrans, South Africa with the loss of 372 of the 378 on board.

- 16 June – Napoleonic Wars: Battle of Quatre Bras – Marshal Ney wins a strategic victory over an Anglo-Dutch force.

- 18 June – Napoleonic Wars: The Duke of Wellington wins a decisive victory over Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo.[

- 21 June – News of the victory at Waterloo reaches London this evening.

- 10 July – Apothecaries Act prohibits unlicensed medical practitioners.

- 15 July – Napoleon boards HMS Bellerophon off Rochefort and surrenders to Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland of the Royal Navy.

- 24 July–4 August – HMS Bellerophon anchors off the south Devon coast with Napoleon on board prior to his being taken into exile.

- 1 August – William Smith publishes the first national geological map of the UK, A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales, with part of Scotland.

- 18 October – The Bible Christian Church, a Wesleyan Methodist denomination, is founded by William O’Bryan in north Devon and Cornwall.

- 3 November – Sir Humphry Davy announces his discovery of the Davy lamp as a coal mining safety lamp.

- 5 November – Ionian Islands become a British protectorate.

And………

- Jones, Watts and Doulton begin life as a stoneware pottery in South London.

- Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack retrospectively recognises statistics for first-class cricket in England from this year.

- Jane Austen‘s novel Emma (anonymous; dated 1816).

- Lord Byron‘s poems with musical settings Hebrew Melodies, including “She Walks in Beauty“; sells over 10,000 copies in a few months.

- Thomas Love Peacock‘s first novel Headlong Hall (anonymous; dated 1816).

- Walter Scott‘s novel Guy Mannering (anonymous).

Born

- 12 February – Edward Forbes, naturalist (died 1854)

- 24 January – Thomas Gee, Welsh publisher (died 1898)

- 24 April – Anthony Trollope, English novelist (died 1882)

- 2 November – George Boole, English mathematician and philosopher (died 1864)

- 10 December – Augusta Ada King (née Byron), Countess of Lovelace, early English computer pioneer (died 1852)

Died

- 8 January – Edward Pakenham, British general (killed in battle) (born 1778)

- 14 January – William Creech, Scottish publisher and Lord Provost of Edinburgh (born 1745)

- 16 January – Emma, Lady Hamilton, English mistress of Horatio Nelson (born 1765)

- 22 February – Smithson Tennant, chemist (born 1761)

- 1 June – James Gillray, caricaturist (born 1757)

- 18 June – Thomas Picton, British general (killed in battle) (born 1758)

Source WIKEPEDIA